Why I Chose the Ross Procedure (and Why I Traveled for It)

Issue #45

Hello! I’m Aaron Kardell. In my newsletter, I pick one random topic to go deep on.

Last week, I shared a reflection on gratitude following open-heart surgery. I mentioned in passing that I would save a separate post for how I ultimately chose the Ross procedure, why I traveled to New York to get it, and why the decision process took as long as it did.

Here’s that story of uncertainty, research, second-guessing, community advice, waiting, and finally arriving at a decision that brought me real peace.

tl;dr

Somehow this post ballooned to over 2,100 words. If that’s not your jam, just read this:

In March, I started researching, assuming I’d end up with a mechanical valve, only to feel increasingly unsettled by early consults, surgeon preferences, and the reality that even some great hospitals have non-trivial mortality stats. The Ross procedure was initially presented to me like a fringe, extreme-sports-adjacent option… until one unsolicited Facebook comment from a cardiac surgeon stopped me in my tracks and made me take it seriously. Once I dug in, I realized the Ross can be a “best of both worlds” outcome, by providing living tissue in the aortic position, no lifelong blood thinners, and great hemodynamics. However, the Ross is only suitable in the right hands at high-volume centers. The turning point was my consult with Dr. El-Hamamsy: within minutes, the emotional weight lifted - his confidence, warmth, and clarity (and his conviction about long-term outcomes) snapped the months of indecision, and I knew I was going to New York. Looking back, it feels obvious, but at the time it was a grind of research, waiting, fear disguised as pragmatism, and prayer for clarity. My biggest takeaway is still this: if you have time, don’t rush; get more opinions; look at the data; listen to lived experience; and don’t underestimate how much it matters to trust the hands you’re putting your life in.

When “Eventually” Becomes “Now”

In my last note, I mentioned that back in March, my cardiologist gently but clearly told me that 2025 needed to be the year for a valve replacement.

In an instant, the theoretical became real. It was time to start the process. Fortunately, my cardiologist framed it as I had enough time to find a surgeon I was comfortable with, and I was grateful for that.

Over the years, I’ve had several cardiologists. Early on, one of them planted a subtle seed that stayed with me for a long time. She said something along the lines of: technology keeps advancing every couple of years, and if you’re lucky, your options may improve by the time you actually need surgery.

The conventional wisdom was always straightforward: when the day comes, you’ll either get a mechanical valve or a tissue valve made from bovine (cow) or porcine (pig) material.

My First Surgical Consult

In April, I had my first formal surgical consult with a respected surgeon in Saint Paul. The meeting followed a predictable structure. He walked through the pros and cons of the two “standard” options: tissue valve vs. mechanical valve.

Tissue valves are rarely considered for younger people like me because they typically only last 10-15 years at best, and you end up having multiple open-heart surgeries.

So naturally, the conversation focused on mechanical valves. They’re designed to last a lifetime. But they come with a significant trade-off: lifelong anticoagulation (blood thinners). And that’s not trivial. It changes how you live, what activities you can do, what risks you carry, and even how minor injuries are handled.

Having done research going into the consult, I assumed I wanted the On-X mechanical valve. It had more recent clinical data suggesting that some patients could safely be on lower levels of anticoagulation, and that the category of drugs might evolve to something more easily managed over time.

What surprised me was how dismissive the surgeon seemed of it. He preferred another brand and was dismissive of the On-X’s benefits, even though most of what I found online suggested that many surgeons were increasingly gravitating toward it.

That disconnect stuck with me.

During the meeting, he briefly mentioned the Ross procedure as an option, but not one he performed. But it was framed almost as an extreme option. If I were into extreme sports and prone to cuts and bruises, I should consider the Ross so I could avoid blood thinners. But it felt like more of an academic footnote than a serious consideration.

I left assuming I’d be getting a mechanical valve, but I was unsettled about the surgeon. I wanted a second opinion from someone who preferred the On-X mechanical valve.

Statistics and Geography

Around that same time, I started looking into hospital performance data.

The best local hospitals had an operative mortality rate for aortic valve replacement of ~2%. Even world-renowned hospitals like Mayo Clinic had an operative mortality rate of ~1.4%. Cleveland Clinic brought that number down to ~0.8%.

I began thinking in probabilities. Even “minor” percentage differences mattered a lot to me when the stakes are this high.

Later I learned my personal surgical risk was lower. Maybe ~0.5% mortality, given my age and it being my first surgery. But once you’ve seen the bigger numbers, you can’t unsee them. And with that, an openness to traveling for surgery took root. I came to believe that choosing the right surgeon and center mattered more than geographic convenience.

Mayo, Mechanical Valves, and the Facebook Comment that Changed Everything

In early June, I went to Mayo Clinic to get a second opinion from another surgeon. This new surgeon preferred the On-X, and he was a comforting presence.

I had some international travel planned for early August, and this surgeon was highly sought after and had limited availability anyway. So, I went ahead and penciled in having surgery in September.

Given that we were in a waiting game and that I was still of a mind to research everything to the nth degree, I asked Kate to ask her physician friends on one of her Facebook groups if anyone had experience with that surgeon at Mayo.

She posted a question asking about the Mayo surgeon I was considering. The feedback was all generally positive. People spoke highly of him.

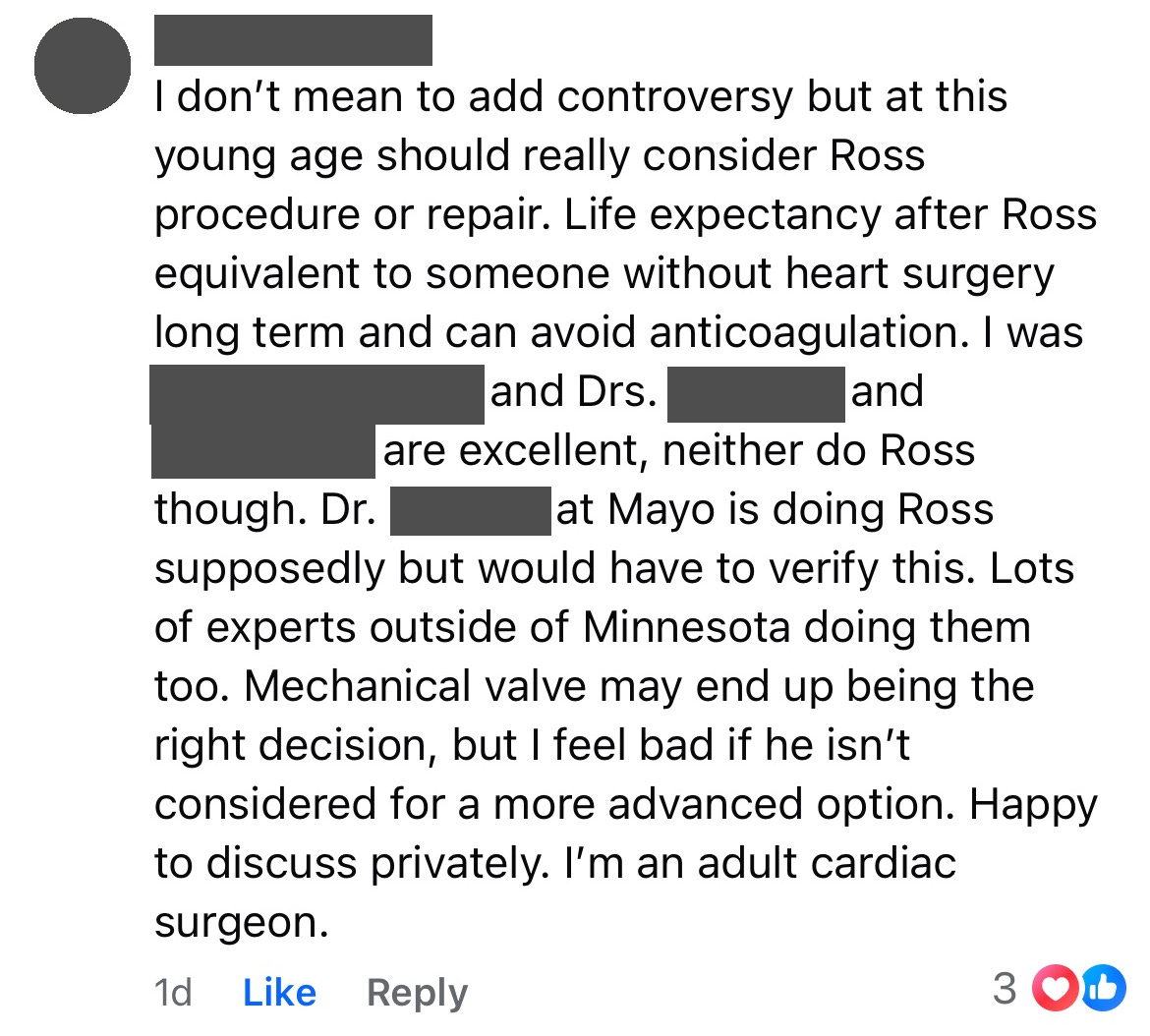

But one response stood out:

That comment stopped us both in our tracks.

Up until that moment, the Ross had felt like a fringe idea. Something that was mentioned briefly and then set aside. But hearing it raised unsolicited by a cardiac surgeon in a neutral setting made me take it seriously in a way I hadn’t before.

That comment became a pivot.

Learning What the Ross Really Is

Once I started digging into the Ross procedure in earnest, I quickly learned two things:

It is significantly more complex than a standard valve replacement.

In the right hands, it offers something close to a “best of both worlds” outcome.

In simple terms, the Ross uses your own pulmonary valve to replace your diseased aortic valve. Then a donor valve replaces the pulmonary valve.

The upside is remarkable: native living tissue in the aortic position, no lifelong blood thinners, excellent hemodynamics, and, if successful, long-term survival that can resemble that of the general population.

The downside is equally real: it is technically demanding, takes longer, and absolutely requires a surgeon who performs a high volume of procedures. Various research papers suggest the morbidity and mortality rates were meaningfully higher for the Ross unless you’re in the hands of a surgeon who has done at least 100 Ross procedures.

This is not a procedure you casually shop for.

As I researched, consistently I heard about the importance of going to a high-volume center if I pursued the Ross. This report from Google Gemini proved to be instrumental in my decision-making - A Clinical Intelligence Report on High-Volume Centers and Surgeons for the Ross Procedure in North America.

That report suggested there were only eight places I should consider getting a Ross procedure in North America. Fortunately, one of those was Mayo!

However, I immediately noted that one option stood head and shoulders above the others – Mount Sinai in New York City.

Trying to Keep All Options Alive

At this point, I decided to run two paths in parallel.

First, I went back to Mayo to figure out which surgeons actually performed the Ross procedure. I quickly confirmed that the surgeon I had been working with did not.

I asked for a referral to the Mayo surgeon who performs Ross operations. That got the wheels in motion, albeit slowly.

Second, I contacted Mount Sinai directly and requested a surgical consult with Dr. El-Hamamsy.

Then began what might have been the hardest non-medical part of the process: waiting.

It took nearly eight weeks from the date the Ross became a serious consideration to getting the surgical consult with the Mayo surgeon who performs Ross. And for a while, it felt like my request at Mount Sinai had disappeared into a black hole.

Those weeks were mentally taxing. I had enough information to know that the Ross might be my best long-term option, but not enough certainty to see if I was even a candidate for it or whether the surgeons at Mayo or Mount Sinai would agree to perform the procedure.

It felt like standing at a fork in the road, unable to see down either path.

Hope and Disappointment

Before the Mayo surgical consult, I had yet another echo, this time with a focus on my pulmonary valve. A comment made by the cardiologist doing the echo gave me a lot of hope that I would be a good fit for the Ross.

Now to wait for the surgical consult. A couple of days before the consult, the surgeon’s scheduler called me and basically implied that the surgeon wouldn’t be recommending the Ross, and asked if I really still wanted to drive down for the appointment.

I said I’d been waiting for this consult for a long time. We could switch to a virtual appointment, but I was keeping the appointment.

The consult that followed was confusing, at best. It was his belief that I might eventually end up on anticoagulants for other reasons, so, in his opinion, the Ross wouldn’t be that beneficial, and he wasn’t recommending it. But then he said, “Why don’t you and your wife talk it over, and if you want me to do it, give me a call, and we’ll get it scheduled?”

What the actual…?

The Call That Changed Everything

I still hadn’t heard back from Mount Sinai at this point, and by this time, I was less than 3 weeks out from my scheduled surgery with the first Mayo surgeon for a mechanical valve. I got to work earnestly to figure out how to get a yes-or-no from Mount Sinai. Thanks to some other Facebook groups that put me in touch with former patients of Dr. El-Hamamsy, I found some faster paths in.

There was still some nominal hope alive for getting the Ross at Mount Sinai, so I called Mayo to postpone my surgery.

I was able to electronically send over all my records to Mount Sinai. By some miracle, a virtual consult call with Dr. El-Hamamsy was scheduled for less than two weeks after the strange “no, but if you really want to, I’ll do it” I had received from the Mayo Ross surgeon.

In the days leading up to the consult with Dr. El-Hamamsy, my wife, my parents, and I were earnestly praying for clarity of direction. We asked that it be abundantly clear which path I should take.

Within minutes of hopping on that Zoom with Dr. El-Hamamsy, the entire emotional tenor of the decision changed.

Dr. El-Hamamsy spoke with the confidence that comes from being the world’s leading surgeon in this field. And yet he came off as deeply warm, empathetic, and caring.

We talked through my anatomy, age, activity level, and goals for the rest of my life.

In no uncertain terms, he told me why he believed the Ross procedure was the best option for me. He adamantly disagreed with the Mayo doctor’s reservations. He got a little fired up in that part of the conversation.

Most notably, he repeatedly emphasized that the life expectancy of Ross patients matched that of the general population.

He spoke with a conviction that only comes from deep experience.

When that call ended, something shifted in me. The indecision that had been swirling for months was gone.

I knew I was traveling to New York for surgery.

The biggest anxiety quickly shifted to “would my insurance try to deny this claim?” And fortunately, it was never an issue. I feel very fortunate.

Why I Ultimately Chose the Ross & Dr. El-Hamamsy

The prospect of a longer life expectancy and no need for anticoagulation drugs was quite compelling in its own right.

But the trust I felt in Dr. El-Hamamsy to perform the surgery after that consult was what tipped the scales. All uncertainty faded away, and quickly.

Although I was very driven by the research and the statistics along the way, it ultimately came down to confidence. I wanted the person operating on my heart to be someone who knows this procedure at an almost cellular level.

Finally, I felt peace about the decision.

Looking Back From the Other Side

Now that I’m on the other side of surgery, recovery, and reflection, the decision feels almost obvious in hindsight.

But at the time, it was anything but.

It was weeks of learning new medical vocabulary. Long conversations with Kate. Reading research that I was under-qualified to be reading. Waiting for calls. Managing probabilities. Wrestling with fear disguised as pragmatism.

I’m profoundly grateful for the physicians who guided me.

For the “random” physician in a Facebook group who spoke up at just the right moment when Kate asked. (Consider: A single Facebook comment from a kind stranger may have added a meaningful number of years to my life! I still can’t get over this.)

For a healthcare system that miraculously made this path possible.

For my parents, Kate, Brad, and various other friends and family who helped us make the logistics work to travel for surgery. And for having the resources to not worry about travel expenses.

For Dr. El-Hamamsy, who treated me not as a case, but as a person. This has quickly become one of my more cherished photos, taken 12 days after surgery at the post-op appointment…